Some of the recent additions to the Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) web standard are so powerful that a security researcher has abused them to deanonymize visitors to a demo site and reveal their Facebook usernames, avatars, and if they liked a particular web page of Facebook.

Information leaked via this attack could aid some advertisers link IP addresses or advertising profiles to real-life persons, posing a serious threat to a user's online privacy.

The leak isn't specific to Facebook but affects all sites which allow their content to be embedded on other web pages via iframes.

Vulnerability resides in browsers, not websites

The actual vulnerability resides in the browser implementation of a CSS feature named "mix-blend-mode," added in 2016 in the CSS3 web standard.

The mix-blend-mode feature allows web developers to stack web components on top of each other and add effects for controlling to the way they interact.

As the feature's name hints, these effects are inspired by the blend modes found in photo editing software like Photoshop, Gimp, Paint.net, and others. Example blend modes are Overlay, Darken, Lighten, Color Dodge, Multiply, Inverse, and others.

The CSS3 mix-blend-mode feature supports 16 blend modes and is fully supported in Chrome (since v49) and Firefox (since v59), and partially supported in Safari (since v11 on macOs and v10.3 on iOS).

Researchers uses a DIV stack to reconstruct iframe content

In research published today, Ruslan Habalov, a security engineer at Google in Switzerland, together with security researcher Dario Weißer, have revealed how an attacker could abuse CSS3 mix-blend-mode to leak information from other sites.

The technique relies on luring users to a malicious site where the attacker embeds iframes to other sites. In their example, the two embedded iframes for one of Facebook's social widgets, but other sites are also susceptible to this issue.

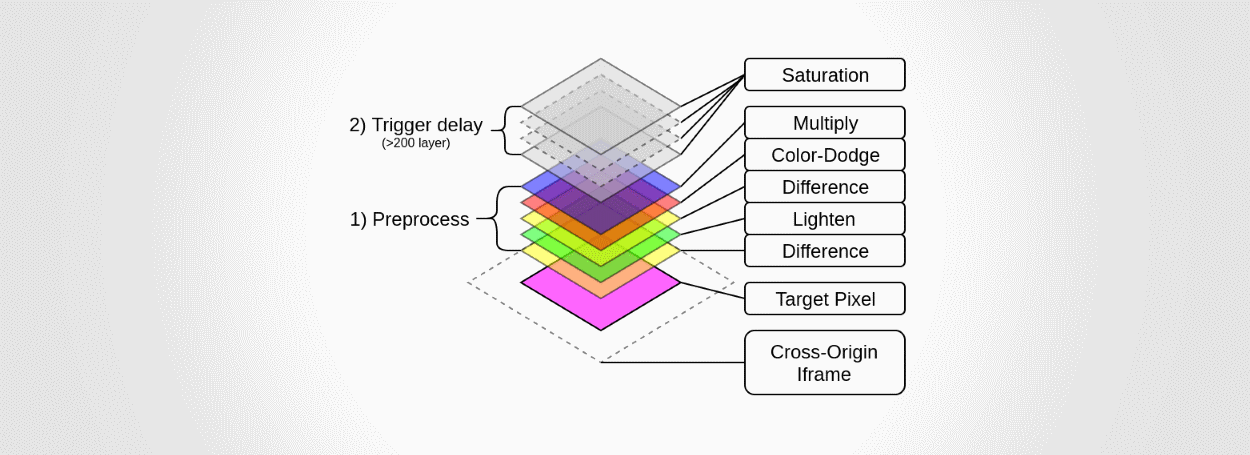

The attack consists of overlaying a huge stack of DIV layers with different blend modes on top of the iframe. These layers are all 1x1 pixel-sized, meaning they cover just one pixel of the iframe.

Habalov and Weißer say that depending on the time needed to render the entire stack of DIVs, an attacker can determine the color of that pixel shown on the user's screen.

The researchers say that by gradually moving this DIV "scan" stack across the iframe, "it is possible to determine the iframe’s content."

Normally, an attacker wouldn't be able to access the data of these iframes due to anti-clickjacking and other security measures implemented in browsers and in the remote sites that allow their content to be embedded via iframes.

Two very impressive demos are available

In two demos published online (here and here), researchers were able to retrieve a user's Facebook name, a low-res version of his avatar, and the sites he liked.

The actual attack takes about 20 seconds to leak the username, 500 milliseconds to check the status of any liked/not-liked page, and around 20 minutes to retrieve a Facebook user's avatar.

The attack is easy to disguise because the iframe can easily be moved offscreen, or hidden under another element (see demo gif below, hiding the attack under a cat photo). Furthermore, keeping a user on a site for minutes is also possible by keeping him busy with an online test or a longer article.

Fixes available for Chrome and Firefox

The two reported the bug to Google and Mozilla engineers, who fixed the issue in Chrome 63 and Firefox 60.

"The bug was addressed by vectorizing the blend mode computations," Habalov and Weißer said. Safari's implementation of CSS3 mix-blend-mode was not affected as the blend mode operations were already vectorized.

Besides the two, another researcher named Max May independently discovered and reported this issue to Google in March 2017.

Comments

PresentFail - 5 years ago

>"Besides the two, another researcher named Max May independently discovered and reported this issue to Google in March 2017."

Then why is this article about these two and why was it only fixed by Google and Mozilla after these two reported it and not Max May?